The Gatehouse: An Emblem of Architectural Englishness

Michael Reiners argues that the gatehouse is an enduring symbol of architectural Englishness. With origins in Saxon Burgh-Geats, enduring into Christian ecclesiastical colleges. For the Tudors, gatehouses become a dynastic and chivalric motif, and later, the emblem of the English parliament.

At various moments throughout history, Tudor architecture has been characterised as inconsistent by its very definition. David Watkin described early Tudor building as “empirical [yet] Picturesque asymmetry”; Mark Girouard pointed to its “happy-go-lucky…approach” while T.G. Jackson remarked, more favourably, that in the Tudor period “art was more free…more joyous” (Watkin 1979; Girouard 1968). Few would equate Englishness and inconsistency as succinctly, or as early, as classical scholar and poet George Chapman (Chapman 1616).

In 1603, the last Tudor, Elizabeth I died; rather poetically, she did so at Henry VII’s Richmond Palace (c.1501), a structure which commemorated the dynasty’s beginnings. Only thirteen years later, George Chapman would characterise Tudor architecture as a “modern barberisme”, imploring Inigo Jones to replace such “monstrous babels” with the “proportionate…ancient architecture” of correct classicism (Chapman 1616; Summerson 1993). The Biblical invocation of Babel and the literary term barbarism (meaning non-standard expression,)suggest Chapman deemed Elizabethan building unpredictable and unable to communicate its core ideas in the academic manner of the classical. It wasn’t up to scratch with the ancients, as he saw it.

Chapman justifiably invoked Babel; England lacked a developed architectural lexicon for describing its built landscape at the time. Architecture and architect were terms introduced to England by John Shute in 1563, after his travels in Italy (Shute 1563; Harris and Savage 1990). For Chapman, no word existed to denote what later historians would call the prodigy-house; he simply understood these buildings as “unjust obscurity” of the correct classical ornament he yearned for in England. In 1615, even Jones could recognise English classicising taste largely in “chimnies peeces &…inner partes of houses”; Chapman desired a classical totality (Summerson 1993; Watkin 1979).

However, the existence of eclectic ornament does not mean the absence of an English architectural language. By the early 1500s there existed an English feature with a historic development and consistency of deployment comparable, in its own way, to the classical orders (Goodall 2012; Howard 1987). That feature is what I have come to call 'the Tudor gatehouse'.

For present purposes, the Tudor or Henrician gatehouse refers to structures of a rectangular plan, featuring octagonal turrets, crenellation and a multi-storey elevation that is either attached or detached from a larger structure, serving as entry-ways or structures in their own right. The detached North-East edifice at Leez Priory is a good model of the gatehouse’s form in isolation (c.1536–40) (Howard 1987; Goodall 2011).

Left: North-East gatehouse at Leez Priory (c.1536–40), Chelmsford, England. Right: Oblique view.

A late-sixteenth-century example clarifies the claim. William Cecil’s Burghley House (c.1558–1587) exemplifies the prodigy-house and also Chapman’s “unjust obscurity” of classical ornament. Competent superimposition of the classical orders can be seen in Burghley’s clock-tower (c.1585), but only on a privileged façade. Outside, only Burghley’s chimney stacks are academically classical, executed in the Tuscan Order, complete with entablature. Conversely, Burghley’s hall was defiantly English, complete with hammer-beam roof. Its East-range entrance references the Henrician gatehouse in formal makeup: rectangular, with four octagonal turrets at the vertices, coursing over three storeys and a crenellated parapet. The parapet is Italianate, while the turrets terminate in a possible reference to the Athenian Tower of the Winds. Classical allusions were present, yet the gatehouse’s overall form was unaffected. Its quality of Englishness persisted.

Left: Burghley House Facade (c.1558–1587), Right: Burleigh House, Clocktower, Privilaged Facade (c.1585)

GATEHOUSES: A BRIEF OVERVIEW, c.1480–c.1600

The gatehouse’s transition from military to domestic building, at first glance, appears limited to the Tudor dynasty. It emerges, domesticised, in the late fifteenth century, commemorating knighthoods. Examples include Sir Edmund Bedingfield’s Oxburgh Hall (c.1482); he constructed his gatehouse in 1483, having been knighted and granted licence to crenellate. Sir John Peche’s knighthood of 1497 coincided with the construction of Lullingstone Castle’s gatehouse.

Crucially, the gatehouse appears where there is no military need and no military past. Saint John’s College, Cambridge, posthumously founded by Henry VII’s mother, is an institution with no martial function, yet features an archetypal Tudor gatehouse (c.1511). Thomas Wolsey’s Hampton Court (begun c.1514) anticipated his promotion to England’s Legate a latere in 1515. Hampton’s West-range has fictive defensibility, being only partially moated and featuring a gatehouse.

Left: Hampton Court West-Range (1514 begun), Right St John's College, Cambridge (c.1511)

Henry VIII’s reign saw the gatehouse become a mainstay seigneurial feature of his inner-circle’s courtier houses. It persisted through the English Reformation and the years of the Italian Renaissance as a defiantly English feature denoting fidelity to the monarch alone. The popularity of gatehouses declined following Henry’s death in 1547; Elizabethan prodigy-houses featured them only occasionally, until the 1580s. At Saint John’s College, Shrewsbury Tower (c.1598–1602), primarily an homage to the neighbouring Great Gate (c.1511–20), marks the end of the gatehouse fashion and also demonstrates the emergence of architectural drawings, here by Ralph Symons (Rawle 1985).

ORIGINS OF ENGLISHNESS: BURH-GEATS, ANGLO-NORMAN GATEHOUSES, AND BATTLE ABBEY

Chapman understood the Tudor as an “unjust obstruction” to the architecturally Roman. Yet for Henry VIII in the 1530s, Rome was the obstructionist, specifically to English political ambitions. Defining Englishness as something distinct from Roman was undoubtedly in the consciousness of the English court; the break with Rome of 1534 made such considerations a necessity. Reform of ecclesiastical and legal institutions linked to Rome became necessary, but to be “comfortable to the spirit of [England]”, Henry and his inner circle faced the difficult task of defining the spirit of England itself. The theological portion of this endeavour was “a turn of the wheel back to the beginning”, necessitating retrieval of Anglo-Saxon records to find a historic basis for a Church of England. Concrete theological links between the Church of England and Anglo-Saxon Christianity were, and remain, scarce. Architectural links between Henrician England and building in the time of Alfred the Great can be demonstrated.

John Goodall points to distinct forms found in Anglo-Saxon architecture which either do not appear in continental Europe, or appear with lesser political importance. Chief among these is the gatehouse. The gatehouse can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon period, appearing in the residences of “Kings, Nobles or Thegns” and referred to as burh-geats, “the gate to the enclosure”. Stephen Harris’s analysis of the term highlights these structures’ importance: in the ninth century a burh was well understood as fortification, while the Geats were known in near-mythological tradition as a tribal race producing heroes of superhuman strength and size. The meaning of burh-geat implies an imposing fortification, and for present purposes, an English origin in contrast to the Roman.

Burh-geats were typically timber, therefore their form is difficult to reconstruct. Yet the type plausibly survives in later stone building. The gatehouse was translated into stone in the eleventh century: Ludlow Castle (c.1080) is an example, and rendered in rubble masonry as in the case of St George’s Tower in Oxford is another. Goodall suggests St George’s is a survival from the defences of the pre-Conquest burh, rebuilt and absorbed into Norman building practice. Herbert Evans’s 1912 survey agrees that rectangular “gatehouse keeps” were a phenomenon of eleventh-century castle design. There is no known continental precedent for large-scale eleventh-century gatehouses of this type or scale, including territories conquered by the Normans. The most plausible explanation offered is evolution from Anglo-Saxon design, materially augmented during the Norman occupation.

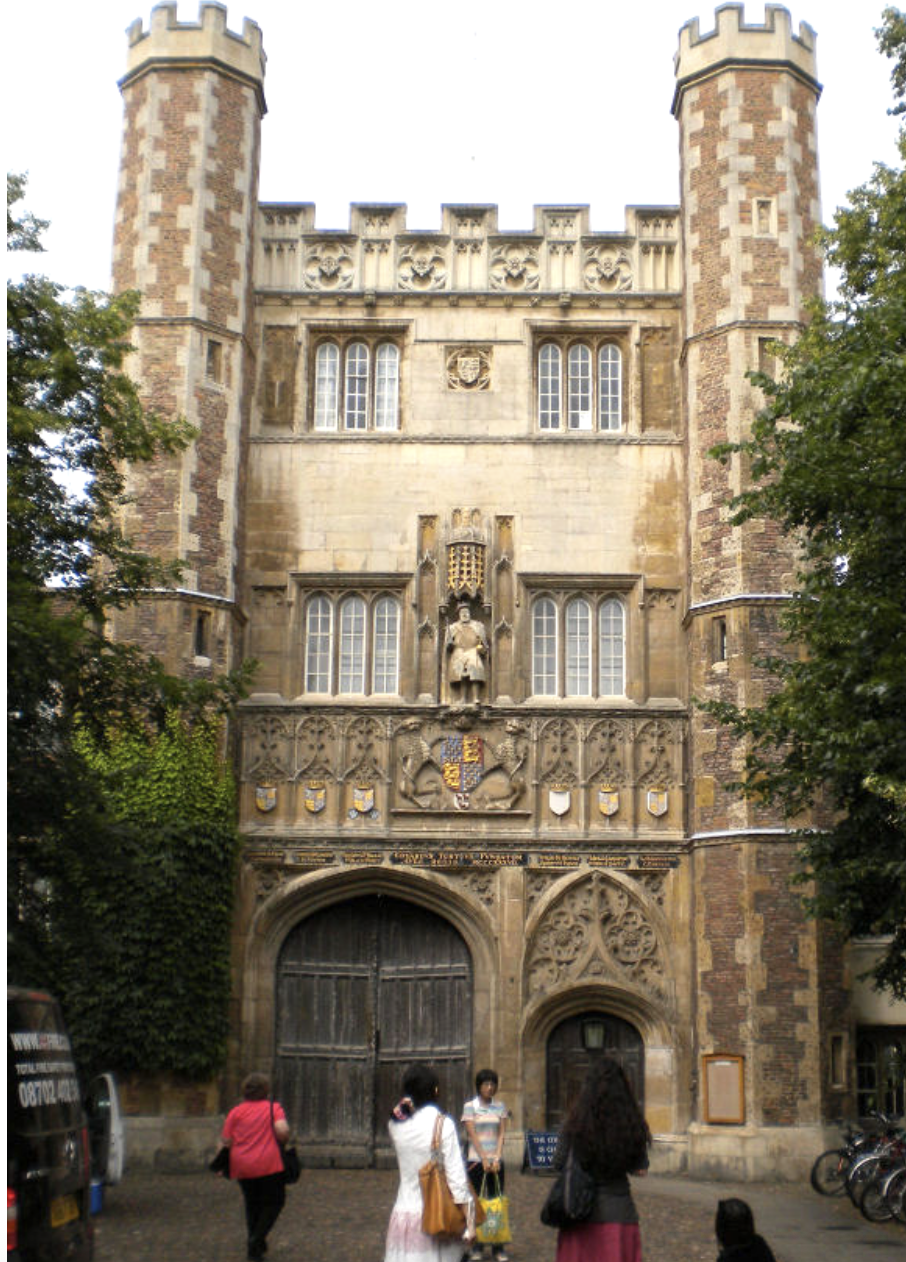

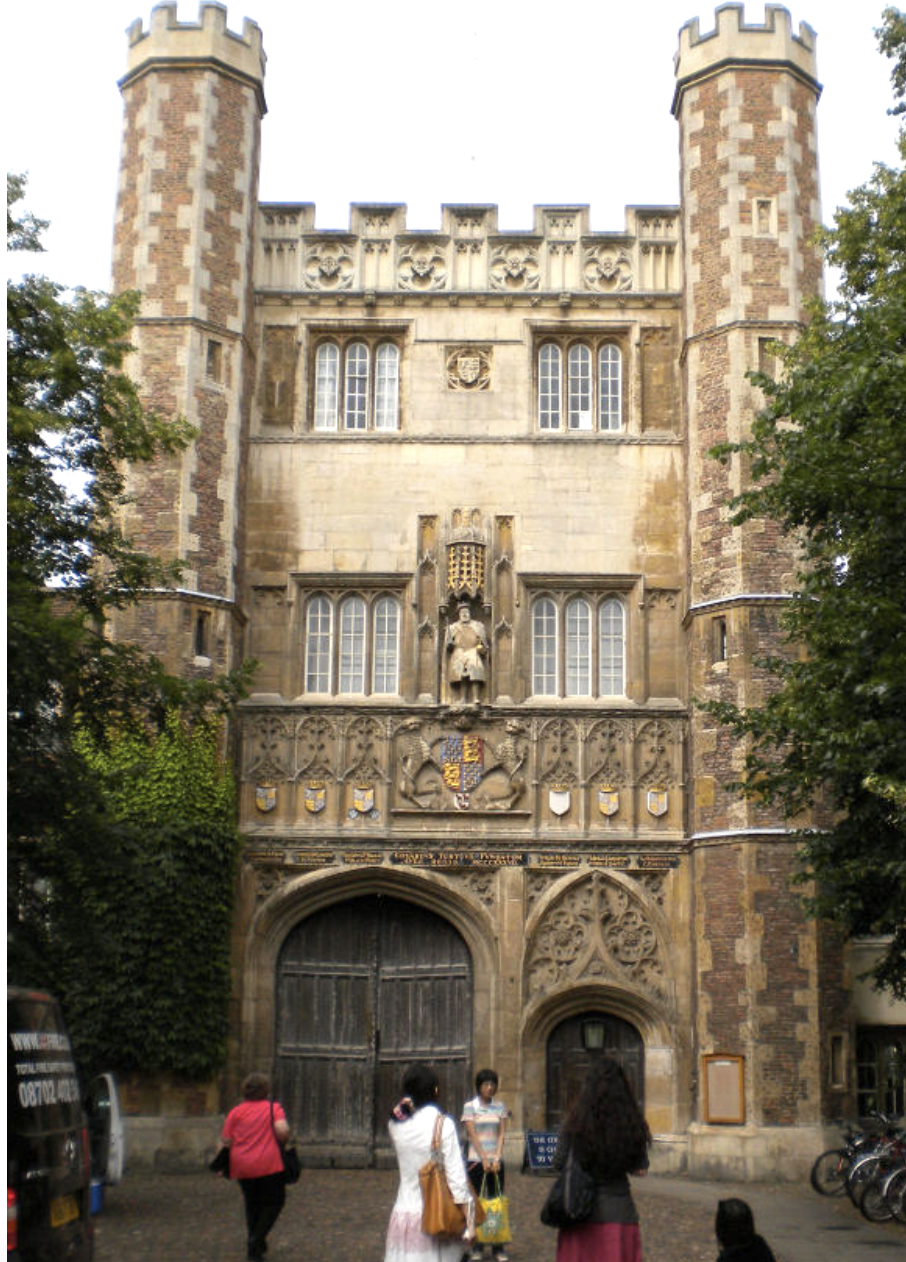

The gatehouse’s military origin is often used to explain its later appearance in domestic Tudor building. Yet there is a further precedent that anticipates the Tudor form with remarkable precision: Battle Abbey’s gatehouse of 1338, constructed on the site of the Battle of Hastings (consecrated 1094). Its appearance here might be read as the point at which the gatehouse became shorthand for a more centralised English monarchy under William I, while also serving as a form of reverence to the fallen Anglo-Saxon king he deposed. The Abbey’s gate bears the same rectangular plan common to Henrician gatehouses. Four octagonal, crenellated turrets appear at the vertices, and the flat, crenellated façade is punctuated by symmetrical Gothic window tracery. Trinity College, Cambridge, Great Gate (c.1518–1535), founded by Henry VIII in 1546, is a near exact replica. John Aubrey later remarked in 1671 that “architecture made no growth but rather went backwards”. Derogatory though it is, it captures a real continuity in this particular form.

Left: Trinity College, Cambridge, Great Gate (c.1518–1535) Right: Battle Abbey, North-range gate, Hastings, begun 1067, consecrated 1094, gatehouse c. 1338

DOMESTICATING THE GATEHOUSE: CASTLES, BRICK, AND COLLEGES, c.1300–c.1520

The gatehouse’s transition from military to domestic is demonstrable. Simon Thurley notes legislation preventing continental workers from entering English masonic circles “since the fourteenth century”. That protectionism provides a context for stylistic continuity and for the persistence of an Anglo-centric building culture in which the mason’s pattern-book held greater sway than the architectural treatise.

In the fourteenth century, Alnwick Castle’s middle-ward gatehouse (c.1309) resembles early Tudor gates in elevation; in plan its twin turrets are D-shaped, not octagonal. Maxstoke Castle’s east gatehouse (c.1345) features twin octagonal turrets, though the later four-turret plan is absent. Pragmatically, these gatehouses are defensible: battlements are accessible; turrets protrude to function as barbicans. Warwick Castle’s gatehouse, added during refortifications (c.1330–60), begins to shift the balance. Its entrance included a gatehouse and a separate barbican; four octagonal turrets appear in the gatehouse plan, and it is ashlar-faced compared to the rusticated barbican, suggesting an increasingly ceremonial function. Maurice Howard questioned the defensibility of late-medieval castles in general, noting that at sites like Bodiam (c.1380s) defences could be “more apparent to the eye than real”.

Left: Alnwick Castle, middle-ward gatehouse, Alnwick, Northumberland, c.1309, Centre: Maxstoke Castle, East gatehouse, North Maxstoke, Warwickshire, c.1345, Right: Warwick Castle, North-East gatehouse, Warwick, Warwickshire, c.1068-1360

By the 1400s, Watkin suggested castles were becoming anachronistic as elaborate living quarters outweighed defence. Brick, once largely confined to domestic buildings like Little Wenham Hall (c.1270–80) and Thornton Abbey (c.1382), later appeared in castles at Caistor and then at Tattershall (begun c.1434). Tattershall, as seen today, takes the form of a 110ft-tall blind gatehouse, built with roughly 322,000 bricks, and was unsuited to defence from newly available cannon. Patron Ralph Cromwell privileged fashion over function, incorporating brick and irregular two-light windows. Pevsner argued for defensibility by functional machicolations, but the upper storeys were reconstructed in 1919 by William Weir, complicating certainty. Kirby Muxloe Castle (c.1480) had gun-posts; Howard argues that in such cases the main concern was poorly armed uprisings rather than siege warfare. At Oxburgh (c.1480s), a domestic structure masquerades as a militant one; its gatehouse retains a barbican style and a single machicolation hole for pouring “hot liquid…on to would-be intruders”, but it never saw use. Tattershall, Muxloe and Oxburgh are domestic households wearing the “fancy-dress” of a castle.

Left: Thornton Abbey, gatehouse, Thornton Curtis, Lincolnshire, c.1382-3. Centre: Tattershall Castle, Tattershall, Lincolnshire c.1434-40. Right: Kirby Muxloe Castle, North-West gate, Kirby Muxloe, Leicstershire, c.1474-1480

In non-military structures between 1300 and 1520, continuity is clearer. St Augustine’s Abbey gatehouse (c.1308) and the incomplete gatehouse of King’s College, Cambridge (c.1441) suggest a consistent domestic gate tradition across more than a century. Brick’s revival eased execution and cost, allowing on-site kilns rather than quarrying, but did not substantially change style (Rawle 1985). The brick-faced gatehouses of Queen’s College (c.1448–9) and St John’s College (c.1511–1520) have near-identical privileged façades. Watkin suggested that Reginald Ely’s work at Queen’s standardised future collegiate plans. The gatehouse’s architectural form changed minimally for two centuries.

From left to right: 1) St Augustine’s Abbey, gatehouse, Canterbury, c.1308. 2) King’s College Gate (Old Schools Site), Cambridge, begun c.1441 3) St John’s College, first court gatehouse privileged façade, Cambridge, c.1511-20 4) Queen’s College, first court gatehouse privileged façade, Cambridge, c.1448

HERALDRY ON THE GATE: QUEENS’, CHRIST’S, AND ST JOHN’S, c.1448–c.1520

In the exteriors of military gatehouses, heraldry seldom appears; in pre-Tudor collegiate gates it is also often absent. Queen’s College gatehouse (c.1448–9) is devoid of the arms of its foundress, Margaret of Anjou. It is in Henry VII’s reign that heraldry emerges as a gatehouse-language. When Lady Margaret Beaufort founded Christ’s College (c.1505) she displayed Beaufort arms and badges above the four-centred arched entrance (restored in 2019) (Linehan 2011). At St John’s College (c.1511–20) Beaufort arms again appear, accompanied by larger rose and portcullis badges. Iconographically, the portcullises of Christ’s and St John’s established a physical link between the Beaufort portcullis as heraldic badge and the gatehouse itself. Its connotations to English castles are deliberate and its accompanying motto, “Altera Securitas”, stresses the dynastic security sought by the Tudor house by associating itself heavily with this military feature.

Left: Christ’s College, gatehouse façade, Cambridge, c.1505, refaced by James Essex c.1770s and restored and repainted in 2019. Right: Queen’s College, gatehouse façade, Cambridge, c.1448.

Recent close inspection at St John’s strengthens the broader point: these gatehouses do not merely wear heraldry, they are sites where dynastic meaning is actively negotiated and, at times, corrected. After restoration of St John’s gatehouse (c.1511), Dr Frank Salmon has suggested that “the inner petals of the roses are carved in a continuous circle”, which has inspired the view that the flowers were intended as Tudor roses, not simply Lancastrian. Saint John’s was posthumously founded by Henry VII’s mother and completed after the coronation of Henry VIII in 1509, so there is a good case to be made that the rose is in fact Tudor, not a Lancastrian as was thought at its last restoration in 1982 (Reiners 2024). Even at the level of a carved petal, the gatehouse remains a dynastic surface where Tudor identity is asserted rather than assumed.

RICHMOND (1497–1501): A DYNASTIC STATEMENT IN CHIVALRIC FORM

Henry VII’s palace of Richmond, completed in 1501 after the 1497 fire at Sheen, is central. It was rushed to completion within four years and commemorated the marriage of Prince Arthur to Catherine of Aragon in 1501, an event planned since the Anglo-Spanish Treaty of 1489. Since it was built with speed, purpose and an audience of continental ambassadors in mind, it can be taken as a good representation of Henry VII’s intended legacy.

Anton Van der Wyngaerde’s drawings (c.1562) show a palace distinctly Tudor. Howard writes that Richmond “extolled well-established ideas of chivalry…re-awakened by the advent of the Tudor Dynasty”. Caxton’s 1485 Book of the Order of Chivalry urged a nobility reluctant for foreign wars to read Arthurian legend, reigniting a chivalric ideal (Howard 1987; Caxton 1485; Strong 1986). Richmond’s “defences” were fictive: battlements and octagonal turrets were inaccessible and capped with lead-covered onion domes and weathervanes; no defensive scheme governed placement; large leaded panel-glass windows were “unsuited to defence”; the surrounding wall was brick, unsuited to cannon (Thurley 1993; Howard 1987).

Richmond’s interior scheme was reported at length in 1501. Thurley describes the period as the “apogee…[of] architectural heraldic decoration”. In the Great Hall, “pictures of the noble kings of this realme in their harness and robis of goolde” were set “between…wyndowes”. In the chapel, decoration included badges of gold fashioned “as rosis, portculles and such” (Kipling 1990; Thurley 1993). The plural “portculles” matters because it points to the Beaufort portcullis motif, adopted into Tudor symbolism, and already being driven hard as a dynastic sign.

THE GATEHOUSE AS BADGE: PORTCULLIS, LICENCE, AND AN “H” IN ELEVATION

The claim can be sharpened. The portcullis proper was seldom used as a functional defensive element by 1500, yet the gatehouse proliferated in Henry VIII’s reign. It is possible to read the Tudor gatehouse as an evolution of the Beaufort portcullis: not simply a badge applied to a gate, but the gate itself becoming badge-like. The link is first established iconographically at Christ’s and St John’s; it is then amplified across collegiate and courtly contexts.

A second reading, specific to the early sixteenth century, concerns the gatehouse’s elevation. Hubert Pragnell noted Elizabethan buildings appearing with E-shaped plans referencing the Queen’s initial, enabled by the rise of surveyors and drawing (Pragnell 1984). In the years of Henry VII and VIII, symbolism appears less in plan and more in elevation. It is a contention that the Henrician gatehouse in elevation resembles an H. Christ’s and St John’s gates enter planning around 1505 and post-date Arthur’s death (1502). Trinity College’s Great Gate (c.1518–1535) carries blind Gothic arcading between turrets that reads like a typographic crossbar; Leez Priory (c.1536–40) uses string courses to similar effect; Shurland Hall’s parapet line can do the same. If an H-reading carried meaning, it also helps explain the gatehouse’s decline after Henry’s death in 1547.

Right: Trinity College, Great Gate, Cambridge. c.1518-1535 Left: Leez Priory (c.1536–40).

Licensing reinforces the badge-reading. Under Henry VIII, Acts of Parliament strengthened restrictions on “aliens” in English guilds, continuing older legislation, and a London masonic circle preserved royal-mason practice. In this environment the pattern-book matters more than the treatise. Andrew Boorde’s 1540 book speaks in terms of “building”, not architecture, and William Harrison (1577) still prefers “building” and “workmen” despite Shute’s earlier introduction of architectural vocabulary (Thurley 1993; Harris and Savage 1990; Van Eck and Anderson 2003). The gatehouse’s regularity over broad geographies points to transmission through practice, under a monarchy that also controlled, withheld and could revoke licences to crenellate.

COURTIER HOUSES AND “BASTARD FEUDAL” DISPLAY, c.1520–1544

In Starkey’s “bastard feudalism”, the heraldic badge, unlike coat armour, could be applied freely to mark “any object, animate or inanimate…as the g” (Starkey 1981). This helps explain why gatehouse display clusters around patronage, office, and proximity to the king.

Before 1534, the gatehouse coincides with favour at court. Henry Marney, favourite and officer, appointed Captain of the Bodyguard in 1521, built Layer Marney Tower (c.1520–23), the tallest gatehouse in England. Sir Richard Weston’s rise through knighthood and entry to the Privy Chamber coincided with receipt of Sutton Manor (after the execution of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, in 1521); Weston’s first addition was a gatehouse (now lost but sketched before demolition). Sir William Fitzwilliam bought Cowdray by 1529; record exists of Henry VIII’s licence to crenellate; Cowdray’s H-shaped gatehouse was added around that time. Its battlements were inaccessible and the gate faced inland, hampering any coastal watch role. By contrast, Henry’s device forts of the late 1530s, built as a genuine coastal defence scheme against invasion, do not use the gatehouse form and do not use brick. The division between real military building and domestic “military” display is explicit.

After the onset of dissolution and redistribution, new gatehouses appear as deliberate additions rather than reuse of monastic fabric. In 1533, Thomas Audley wrote to Cromwell demanding a residence befitting his office as Lord Chancellor, making the link between office and architecture explicit. Sir Richard Rich acquired Leez Priory in 1536 and constructed two gatehouses (one attached, one detached), in brick. Gervase Clifton at Hodsock Priory likely built his gatehouse before summer 1541 to greet Henry VIII at knighthood. Thomas Wriothesley, made secretary of the Privy Council and knighted in 1540, likely built Titchfield’s attached gatehouse that year; Leland’s Itinerary remarks that Wriothesley “hath builded” a house “embatelid…with goodley gate” (Knowles 1976). By 1544 Wriothesley replaced Audley as Lord Chancellor. Rich, likewise, held office tied directly to monastic revenues and testified against or aided the falls of senior figures. Across these cases, those most associated with gatehouse display are also those most enmeshed in and loyal to the Crown’s shifting priorities and personnel in the 1530s and 1540s.

BODYPOLITIC: HOUSEHOLDS AS POLITICAL UNITS AND ARCHITECTURAL “UNIFORMS”

Dr David Starkey asserts that the household was the “primary social and political unit” of England. If so, the architectural marking of households mattered. Sir Thomas Smith’s The Common Wealth of England (1565) treats noble households as attached to the monarch as though they were “members of his owne body” (Smith 1565). Whatever later theorising one prefers, the mechanism here is concrete: a centralising monarchy, licensing control, patronage, and a repeatable built form that signals delegated status.

The social stakes of loyalty are illustrated in anecdote. Henry VIII publicly informed Sir William Butler, who defected to Buckingham’s service, that “none of his servants should hang on another man’s sleeve”, and Butler was described as trembling. Maurice Howard describes the “splendid house” as a “uniform” for the inner circle, much like the king’s colours worn at court (Howard 1987). The gatehouse is the most demonstrable part of that uniform: more regular than “picturesque asymmetry” implies, widely legible, and in its heraldic and typographic readings, capable of acting like an architectural badge.

RENAISSANCE PRINCE OR CONTINENTAL DISSENTER: CLASSICISM WITHIN AN ENGLISH FRAME

Henry VIII cultivated continental learning and personnel. He spoke and wrote French, Italian and Latin, employed foreign craftsmen and musicians, and understood the prestige economy of Renaissance Europe, as the Field of Cloth of Gold (1520) demonstrated. He also stood close to the papacy before the breach: Leo X awarded him the Blessed Sword and Hat (1513) and the title Defender of the Faith (1521) after the Assertio Septim Sacramentorum (Reiss 2012). Presentation copies of that work display classical awareness in typography and ornament. Yet “real knowledge” did not correlate to building “in the manner of the ancients”. Descriptors remained “grand”, “goodley” and “faire”. “Antik” appears in English around 1516, but “architecture” does not.

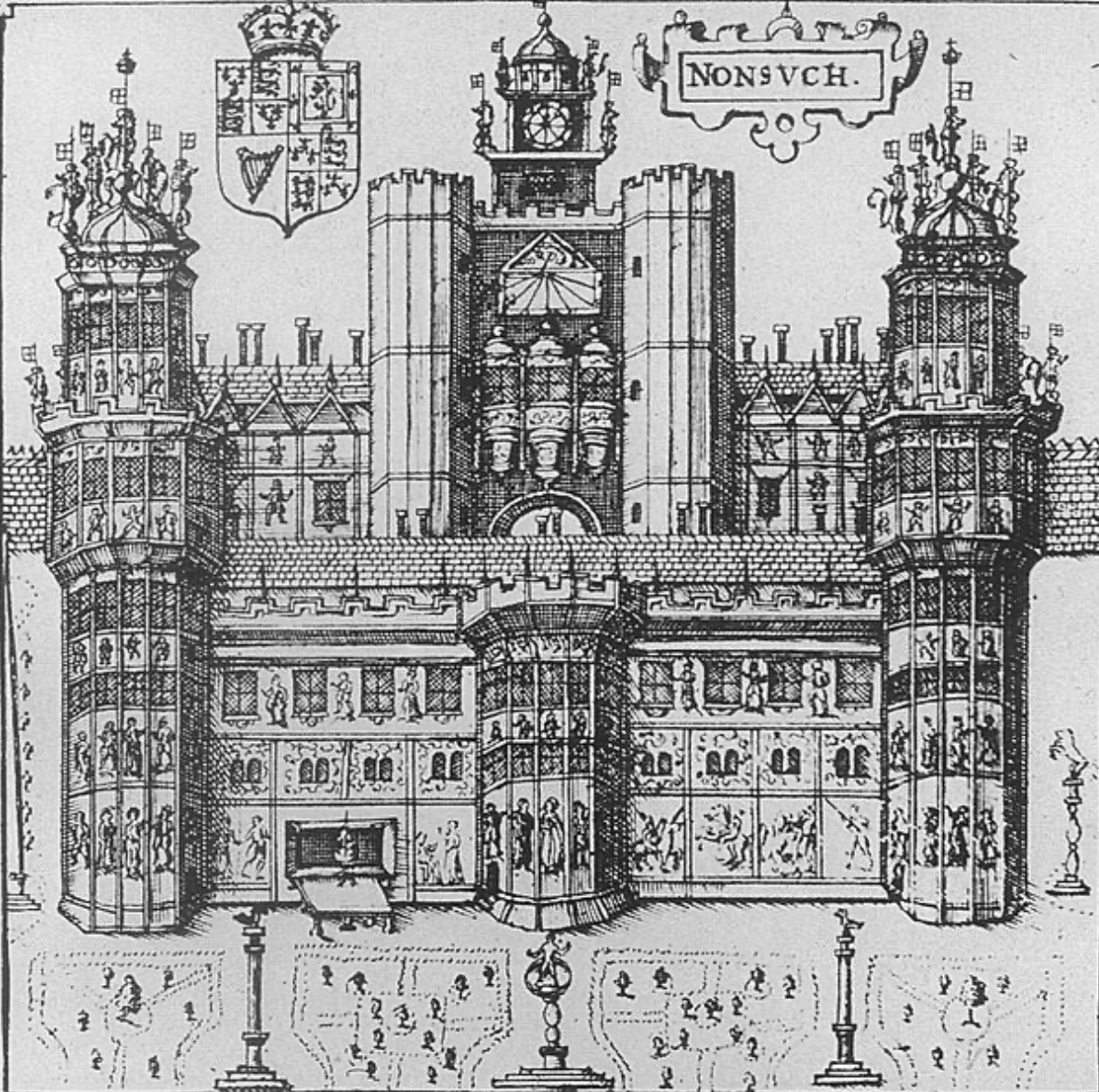

This tension is most revealing at Nonsuch. Henry’s most classical project, it was also framed by the gatehouse type. Nonsuch is lost, but descriptions of its second court suggest a sculptural scheme rivalled “Romane antiques” and a programme of around 92 near-life-size classical figures, with “Henry…with his son Edward” at its centre. Yet its northerly approach featured two austere H-shaped gatehouses, one at the entrance and one between courts. Evelyn described the first court as “Castle-like” and the second as a “Gothique fabric”. The south range, the most classical, can be read as a monumental gatehouse smothered in panelled display with orders superimposed upon octagonal turrets. Even here, the classical is framed by a recognisably English, pseudo-military threshold.

By the 1570s, treatises (Serlio, Hans Blum) appear in gentry inventories, indicating increasing literacy in continental architecture. Yet the gatehouse persists as a framing device. At Tixall Manor (c.1580), the rectangular gatehouse with crenellated octagonal turrets remains, now with Doric columns flanking the entrance and higher orders layered above; the gatehouse becomes a canvas for classical superimposition rather than a form to be discarded. At St John’s, Shrewsbury Tower (c.1598–1602) stands as an explicit late homage to the Great Gate, demonstrating both the end of the fashion and the durability of the form’s prestige.

POST-TUDOR LEGACY: RUINS, PARLIAMENT, REVIVAL, AND LEGACY

Outside Jones’s circle, Tudor building was slow to fall out of favour, but in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it was frequently maligned as non-architectural by increasingly classicising standards. In 1624 Henry Wotton remarked the Doric was “rather good Heraldry, than of Architecture” (Wotton 1624). In 1769 Horace Walpole wrote that in Elizabeth’s reign there was “scarce any architecture at all”, meaning few pillars (Walpole 1769). Tudor and Elizabethan building were treated as something other than architecture properly so called.

Ironically, the gatehouse re-emerged in eighteenth-century follies and sham ruins: Castle Hill (c.1742–46), Sanderson Miller’s Sham Castle (c.1762), Clent Castle (c.1780–90s). These are commonly termed “castles” but are often effectively gatehouses, with synecdoche at work. Frank Salmon describes an emerging “cult of the ruin” (Salmon 1999). Whether such structures were monuments of ridicule and destruction or picturesque mementos, they relied on the same shorthand: a gatehouse silhouette that could evoke an English past and a landowner’s dignity – these implied a history tied to the lands, as a matter of fashion statement. What better way to illustrate your long-lived roots in England, than a gatehouse?

Left: Sham Castle, sham-ruined gatehouse designed by Sanderson Miller, Bath, Sommerset, c.1762. Right: Clent Castle, eighteenth century sham-ruined gatehouse, Clent, Worstershire c.1780-1790s

By the early nineteenth century, the Tudor returned explicitly as “Englishness”. Leeds Castle in Kent was remodelled in Henrician fashion around 1822. In 1835, guidance for competitors designing the Houses of Parliament restricted acceptable styles to “Gothic or Elizabethan” on grounds of “Englishness”. Charles Barry introduced the portcullis as the symbol of Parliament at this time, and it remains so (Port 1976). By 1839 Henry Shaw stated it was “no longer necessary to apologize” for attachment to Elizabethan and Tudor styles. Salvin’s Harlaxton Manor (c.1831–37) directly homages Burghley House, with borrowings from multiple prodigy houses (Summerson 1993).

Even claims of finality are risky. Girouard suggested that by 1900 there was an “end of any likelihood” of another Tudor revival, yet Castle Drogo (c.1911–1930), reluctantly designed by Lutyens, revives a stern, gatehouse-like threshold.

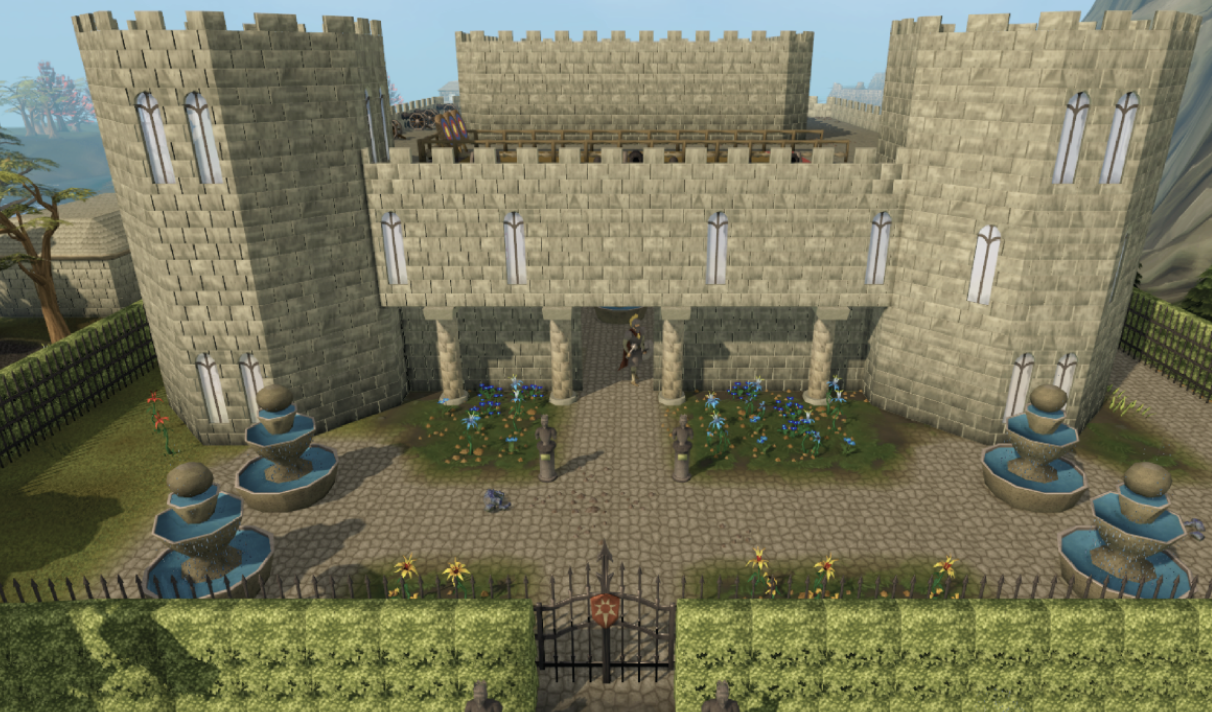

The most unlikely afterlife is digital. In Cambridge in the late 1990s, Andrew, Ian and Paul Gower developed Runescape, released in 2001. By July 17th 2006 it reportedly had “nine million active free players and 800,000 paying members”; by 2012 it held the record as the “world’s most played free-to-play MMORPG” (Leander and Mills 2007). The architectural claim is the important one: to evoke an Arthurian, chivalric European past, the Gowers turned to motifs of Tudor patronage familiar in Cambridge, rendering octagonal-turreted gatehouses throughout the game world. Camelot in Runescape is compared with Windsor Castle’s so-called Henry VIII Gate (c.1511). “River Lum” and “Lumbridge” are presented as explicit nods to Cambridge and the River Cam. The gatehouse remains a legible shorthand for Englishness across media, centuries, and audiences (Leander and Mills 2007).

Left: Hodstock Priory Gatehouse view of the privileged façade, Nottinghamshire, c.1540-41 Right: Render of the façade of ”Lumbridge Castle” by Jagex inc. game Runescape,

Left: Windsor Castle’s Henry VIII Gate, built following the death of Henry VII, Windsor, Berkshire, completed c.1511 Right: Render of the Gatehouse of ”Camelot Castle” from Jagex inc. game Runescape, designed c.1999-2001

CLOSING CLAIM & LEGACY

Chapman’s Babel diagnosis was accurate in one sense: early modern England did not possess a treatise-driven classical lexicon comparable to Italy’s. Yet it did possess a coherent and repeatable English motif, with deep English roots and a specific Tudor political use (Goodall 2012; Thurley 1993). The gatehouse can be traced from burh-geat to Anglo-Norman gatehouse keep; it takes a decisive fourteenth-century form at Battle Abbey (1338); it stabilises in collegiate and domestic gates (c.1308–c.1520); and it proliferates under Henry VII and Henry VIII in contexts tightly correlated with licence, office, patronage and the Reformation settlement (c.1501–1547). Its later recurrence, from Parliament’s portcullis to revival building and digital Camelot (Lumbridge Castle's gatehouse), shows that this form remained a durable, legible token of Englishness long after its defensive function became obsolete. The gatehouse, as set out here, is an English treasure.

REFERENCES:

Caxton, William. 1485. The Book of the Order of Chivalry. Westminster: William Caxton.

Chapman, George. 1616. The Divine Poem of Musaeus. London: Printed by Isaac Jaggard.

Goodall, John. 2011. The English Castle. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Goodall, John. 2012. “The English Gatehouse.” Architectural History 55: 1–23.

Harris, Eileen, and Nicholas Savage. 1990. British Architectural Books and Writers: 1556–1785. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Howard, Maurice. 1987. The Early Tudor Country House: Architecture and Politics 1490–1550. London: George Philip.

Kipling, Gordon, ed. 1990. The Receyt of the Ladie Kateryne. Early English Text Society, Original Series 296. Oxford: Published for the Early English Text Society by Oxford University Press.

Knowles, David. 1976. Bare Ruined Choirs: The Dissolution of the English Monasteries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leander, Kevin, and Steven Mills. 2007. “Transnational Development of an Online Role Player Game by Youth.” Counterpoints 301 (Literacy Research for Political Action and Social Change): 177–195.

Linehan, Peter, ed. 2011. St John’s College Cambridge: A History. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

Port, M. H., ed. 1976. The Houses of Parliament. New Haven: Published for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (London) by Yale University Press.

Pragnell, Hubert. 1984. The Styles of English Architecture. London: B. T. Batsford.

Rawle, Tim. 1985. Cambridge Architecture. London: Trefoil Books.

Reiners, Michael. 2024. “Gatehouses, a thread.” X (posts), 4 November 2024.

Reiss, Sheryl E. 2012. “From ‘Defender of the Faith’ to ‘Suppressor of the Pope’: Visualizing the Relationship of Henry VIII to the Medici Popes Leo X and Clement VII.” In The Anglo-Florentine Renaissance: Art for the Early Tudors, edited by Cinzia Maria Sicca and Louis A. Waldman, 235–264. New Haven: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Salmon, Frank. 1999. “The Cult of the Ruin.” Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain Newsletter 67 (Summer): 10–11.

Smith, Sir Thomas. 1565. The Common Wealth of England. Written 1565, first published 1583.

Starkey, David. 1981. “The Age of the Household: Politics, Society and the Arts c.1350–1550.” In The Later Middle Ages, edited by Stephen Medcalf, 225–290. London: Methuen.

Strong, Roy. 1986. Art and Power: Renaissance Festivals 1450–1650. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

Summerson, John. 1993. Architecture in Britain 1530–1830. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Thurley, Simon. 1993. The Royal Palaces of Tudor England: Architecture and Court Life, 1460–1547. New Haven: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Van Eck, Caroline, ed., with supplementary text by Christy Anderson. 2003. British Architectural Theory 1540–1750: An Anthology of Texts. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Walpole, Horace. 1769. Letter (1769), quoted in Letters of Mr. Walpole, Dr. Ducarel, andc.

Watkin, David. 1979. English Architecture: A Concise History. London: Thames & Hudson.

Wotton, Henry. 1624. The Elements of Architecture. London: John Bill.

Girouard, Mark. 1968. “Attitudes to Elizabethan Architecture, 1600–1900.” In Concerning Architecture, edited by John Summerson, 13–27. London: Penguin.