A Traditionalist, Restorationist Hybrid Model for House of Lords Reform

Leigh Quilter presents a way to come full circle on House of Lords reform, his proposal recognises that legitimacy comes from constitutional balance and the affections of the public; not just democracy.

While the Commons must bray like an ass every day

To appease their elected hordes

We don’t say a thing till we’ve something to say.

There’s a lot to be said for the Lords”

A. P. Herbert - “Big Ben”

Introduction

Following a recent chat about some old ideas for a traditionalist-friendly, restorationist hybrid model for House of Lords reform in had posted on X, I was encouraged to write them up into something resembling a policy paper. This is what you see before you.

I should say from the outset that I have no legal background, nor any special constitutional knowledge which should qualify me to speak on such matters. I merely hope to spark a debate and I very much welcome refinements of my ideas.

I did spend some time in the late “noughties” campaigning against the disappearance of the hereditary peers, including attempting to convince sympathetic peers and MPs to take up the cause again. My hope had been that we might spark restorationist sentiments in the Tory Party in anticipation of them then acting upon them when back in power. I always argued that the interregnum between Charles I and II was eleven years, so if we managed to reverse the House of Lords Act (1999) by about 2010, that it would not be without historical precedent. I failed to convince even the late, great Earl Ferrers that there was any hope, so nothing ever came of that.

Much water has disappeared under the proverbial bridge since then, so it might be tempting to think that there is even less hope for our cause, and yet I am buoyed by rising restorationist sentiment out in the country.

Background

Aristotle wrote “the better mixed a constitution is, the longer it will last.” Ever since I first became politically aware in the 1990s it seems our political elites have been trying their hardest to make our constitution decidedly unmixed. New Labour, ever the iconoclasts, began tearing into our constitutional settlement soon after coming to power in 1997 with the disastrous consequences clear to see all around us.

The House of Lords was one of their main targets. Like with the ban on fox hunting, it was primarily driven by class spite and a desire to rid the Lords of what they perceived to be a Big C Conservative majority, though they never openly admitted this.

Until 1999, all hereditary peers had been entitled to sit in the Lords alongside the Life Peers. It is true this meant our second chamber had a ludicrous number of peers entitled sit and vote, however space in the Chamber was not the main reason New Labour cited before removing all but ninety-two of them in 1999.

Their reason was the hereditary principle, the same principle underpinning our monarchy. Speaking in the Lords during the second reading of the House of Lords Bill, Lord Irving confirmed this by saying “what this Bill is about is the hereditary principle itself. It is about the central contemporary case for removing the right of hereditaries to sit and vote; that membership of this House must be a privilege to be won, not a right to inherit and enjoy.”

What those in New Labour failed to realise was that the House of Lords was so great precisely BECAUSE it was not democratic.

In the foreword to a policy pamphlet entitled The Preservation of the House of Lords produced for the Conservative Monday Club in 1991, Sir John Stokes MP wrote “many peers were trained for their job from birth. They are certainly devoid of ambition and they do not have any “side”. They get into the Lords certainly by accident of birth and it is remarkable how well this random selection process works. We also of course have a hereditary monarchy, and the Lords is but an extension of this.”

The real-world results of the hereditary system seemed to support Sir John’s claims. In 1973, Lord Sudeley, introduced a debate on banning the unlicensed export of historical manuscripts which might be thought valuable to the nation and to prevent documents that might be thought of as part of an important whole being sold off piecemeal. Suffice it to say, it’s unlikely you would find this sort of consideration emerging from the House of Commons.

Hand on heart, if I could sweep away the House of Lords Act 1999 I would. In fact, if I could I would probably scrap the 1958 Act that introduced the current system of Life Peers as well. The arch traditionalist and romantic in me would be quite happy to see an entirely hereditary Lords again, regardless of what quality it yielded. It would also be tempting to counter leftist class spite with traditionalist counter spite. Sir John Stokes also wrote in his foreword “from time to time I hear about reform of the House of Commons, but not once have I received a letter from constituents suggesting reform of the House of Lords.”

However, my head tells me we should perhaps think about it a little more and wonder whether there is an opportunity to create an even better second chamber; one that cherishes the history of the House of Lords and also delivers a chamber fit for centuries to come.

The Opportunity

I find it problematic to say the least that we have a constitution where one house can legislate to change the composition of the other. We say that Parliament is sovereign, but really the House of Commons is sovereign, and short of having a codified constitution where this becomes impossible, I see no way around this.

The best we can hope, therefore, is to arrive at a place vis a vis the Lords where everybody is happy and the House of Commons sees no reason to tinker any further. Aristotle wrote that the constitution would be kept stable “only when no section whatever of the state would even wish to have a different constitution”.

Herein lies our opportunity. Where New Labour blindly sought to introduce democracy for democracy’s sake, we Restorationist should be outlining a vision for a second chamber and a wider constitution that maintains a bridge to our history, preserves balance, injects wisdom and independent thinking and crucially commands the respect and even the affections of the public and the elites alike. We should seek to create a model fit for the next thousand years.

David Starkey has referred to the 1216 version of Magna Carta as counter-revolutionary “conservative” document. By this he means conservative with a small-c. I firmly believe that an ancient country such as Britain is should have a conservative constitution. In respect of the House of Lords, I believe such a constitution could look something like as follows:

A hybrid chamber of six hundred and fifty peers with a one third, one third, one third mix of hereditary, appointed and elected peers chosen by proportional representation. The twenty-six Church of England Bishops should continue to sit and the twelve Law Lords should be restored. For want of a better description, I’d describe this model as “Tripartite Plus”.

I think it’s also worth adding here that I also think there should be a minimum age requirement of thirty-five years for all peers, including the hereditary and elected ones. The aim should be to achieve the maximum amount of wisdom and life experience and for to become starkly different from the House of Commons where ambitiousness, sharp elbows and blind loyalty are often the most rewarded qualities. The US Constitution stipulates a minimum age of thirty-five for standing for the Presidency. I see no reason why we shouldn’t adopt that approach in Britain.

At this point I’d also like to say a brief word against the idea that we should simply do away with the Lords entirely and have a unicameral parliament. The job of a well-mixed and well-balanced constitution is to achieve the best possible law and governance. A unicameral chamber is a way to ramrod the will of the people through, without any wisdom, tempering or restraint. I believe this would be a terrible mistake. As Andrew Tyrie pointed out in his contribution to The Rape of the Constitution: “The Constitutional arguments for second chambers are well-known. Diffusion of power is better than its concentration. Freedom is better protected when it is not entirely dependent on one institution, as it is to the extent that the sovereignty of parliament is coming to mean the sovereignty of the Commons. No doctrine of the separation of powers buttresses freedom in Britain – we remain uncomfortably dependent on the restraint of the executive.”

Throughout what you are about to read, you will notice I will use the phrase “we could”, rather than “we should”. This is because I know there will be people far more qualified than myself who may notice faults in my reasoning, or who simply wish to have a say. I enthusiastically welcome their input.

Two hundred elected peers (the democratic bit)

Following the deliberations in Parliament after the 1999 Act was passed, the various models put forward to Parliament often faltered on the issue of how far to go in introducing an elected element to the Lords.

The simple-minded fetishisation of democracy for democracy’s sake was what had motivated much of the spite against the hereditary system, and yet when faced with the prospect of creating a chamber with even more democratic legitimacy of the House of Commons itself MPs baulked. Labour MP Gerald Kaufman argued that an elected rival House of Lords would be a “constitutional mess”, risked being “some sort of clone” and might produce “gridlock”.

What I propose is a way of satisfying the thirst for greater legitimacy in the House of Lords in a way that politicians of all stripes will hopefully find palatable.

There is no denying that there are serious calls for Proportional Representation in our society, both from Left and from Right. What I propose is a way of introducing an element of democracy into the Lords, while at the same time scratching the PR itch, but all in a way which doesn’t threaten the democratic primacy of the Commons and its ability to create definite, decisive outcomes and stable governments via our tried and tested First Past the Post system.

The way to do this is to create a significant elected element, but one essentially equal to the other major components of the House of Lords. I therefore propose two hundred elected peers determined by open list regional proportional representation.

Two hundred is an important number here. It gives us the ability to divide our regions into even numbers and means when we have staggered elections each region is elected in full, rather than, say, 1 ½ regions being up for election at any given point.

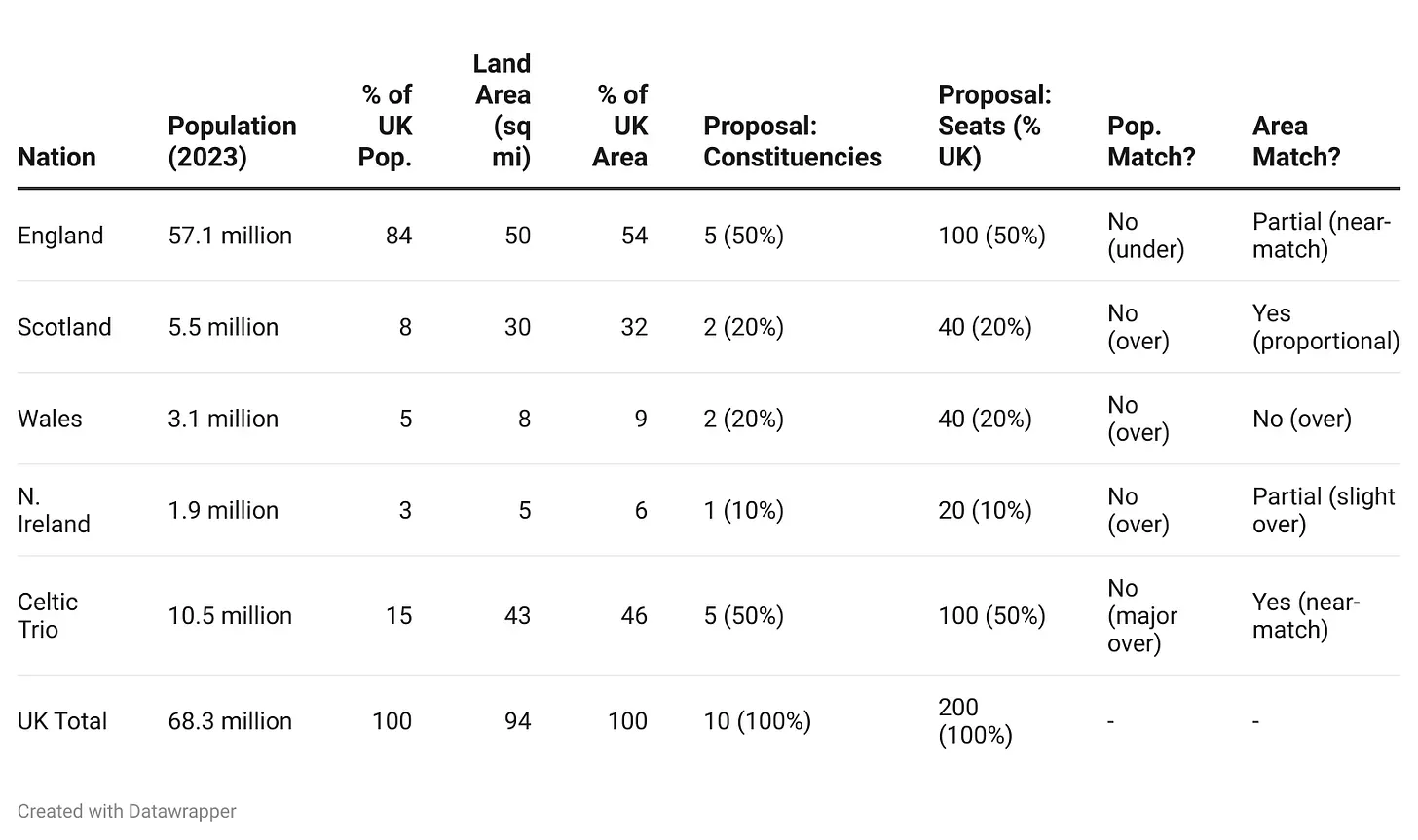

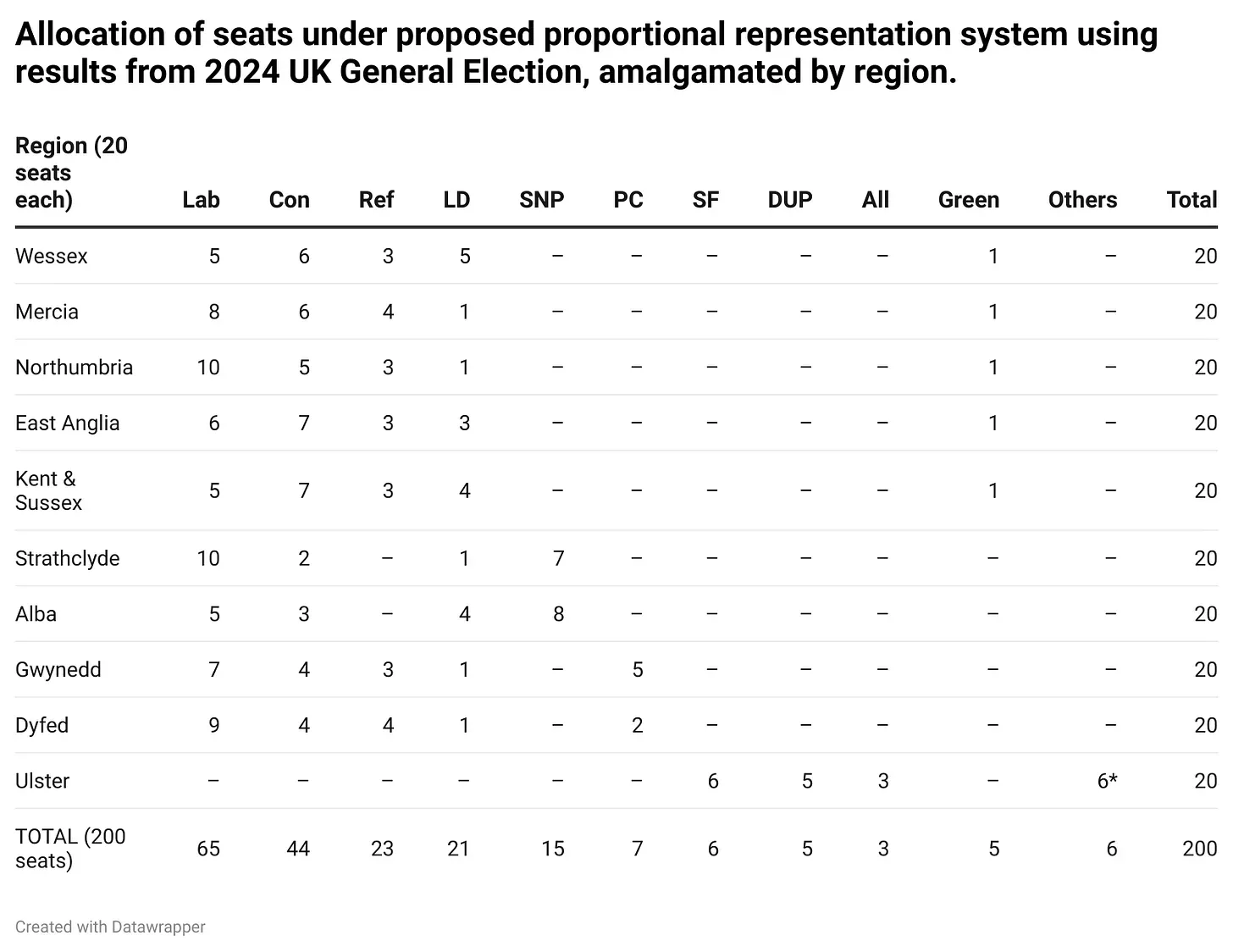

If we split the country into ten regions (in European Election we had twelve), this would give each region twenty elected peers, which would amount to double the “resolution” that the South East of England once enjoyed in European Parliament election.

Although there was a democratic deficit just by being in the European Union in the first place, I do not recall there ever being any complaint that the MEPs we did have did not accurately represent the electorate. By having twice as many elected peers per region, we can ensure far better representation of minority parties and opinions.

A crucial component of this system would be that each of the regions would be granted an equal number of peers regardless of population size, meaning that raw geography is given some power and we can avoid metropolitan dominance.

This sort of model is not without international precedent. The Australian Senate is made up by twelve senators from each of the Federal States, regardless of population. This compromise was made to stop more populous states from dominating the less populous ones, such as Tasmania. The United States Constitution was crafted to ensure territorial representation as well as individual representation and as such the Senate contains two senators from each state, regardless of how populous that state is.

Even the US Electoral College system enshrines the principle of giving power to geography. By ensuring that states voting intentions remain intact and aren’t submerged by a raw democratic majority, each US State retains a distinct political voice. This, again, was a very deliberate choice by the framers of the US Constitution, arguably some of the finest political philosophers in history.

In Federalist Paper no.39 James Madison wrote “Each State, in ratifying the Constitution, is considered as a sovereign body, independent of all others, and only to be bound by its own voluntary act. In this relation, then, the new Constitution will, if established, be a FEDERAL, and not a NATIONAL constitution.” Although we do not have a federal system in the same sense as America does, one can see the benefits of ensuring the nations and regions of Britain are represented in a similar sort of way and that each cannot be trampled by the others.

What model?

Our regions could mirror the ancient regions and kingdoms of the United Kingdom in some way to provide a further sense historical continuity. Starting in the south east we could have Sussex/Kent, then Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria. The into South Wales we’d have Dyfed and moving north Gwynedd. Scotland would have Strathclyde in the South and Alba in the North. Finally, Northern Ireland would have Ulster.

This distribution of constituencies means that the least populous Scotland, Wales and Ulster have equal representation to England, meaning a “Celtic Trio” is created to balance Anglo-Saxon dominance. These three countries combined account for roughly 46% of the land area, but only 16% of the population, so it’s a very good deal for them and hopefully for the stability of the Union.

Northern Ireland, despite only having one of the ten available seats, would have a 7x over-representation per capita. It is home to only 2.8% of the total population and yet would have 10% of the seats available. England on the other hand gets 50% of the available seats for its 84% of the population.

You will also notice that London quite deliberately does not constitute its own region, with different areas of the city falling into Kent/Sussex, Wessex and Mercia respectively. This is another important way to avoid metropolitan thinking.

Option A: We would have a “foundational intake” of all two hundred in an initial Great Election and then begin holding elections for two regions at a time (forty seats) every four years after year twenty. This would mean that the last batch to face re-election would have served for 36 consecutive years. Beyond this the cycle continues as normal, with standard twenty-year cycles, in perpetuity.

Option B: We fill the offices of the elected peers gradually starting at year zero, with elections every four years for two regions at a time (forty seats) and then simply continue the cycle again after twenty years.

Both systems mean an in-built term of twenty years’ service for peers, albeit with an initial bonus period for some of the foundational intake with Option A. By opting for a four-yearly period for elections, we have maximum continuity by ensuring an 80% carry over of existing elected peers each cycle.

Under this system I’d propose retaining a portion of the existing Life Peers and arrange them into “batches” who would then continue to sit until their replacements are elected.

Benefits of both systems

Both models mean long careers would be served without having to face voters, but I think this is the price to pay for continuity and wisdom.

A hypothetical peer elected at the minimum age of thirty-five and falling into an intake batch serving a full thirty-six-year initial term would be seventy-one when up for re-election. If they then served a second term they would finish at ninety-one. Although it would probably be an unnecessary rule, I do think we should stipulate a two-term limit for all elected peers.

Despite the long terms served, both models ensure frequent elections take place and at pre-determined intervals to boot. This would inevitable mean we’d occasionally have something like the American mid-terms, with Lords elections falling somewhere during a normal general election cycle. This would have the power to cause upset and discomfort for the governing part in the Commons; never a bad thing in a healthy democracy.

All this would mean we would get a serious injection of insurgent and smaller parties into the Lords, giving things an occasional shake up and hopefully allowing new ideas to percolate through into the Commons.

We can only wonder how many important issues that were ignored over the years might instead have found an outlet if only there had been some brave, radical peer in the Lords prepared to break silence and introduce that issue into the discourse and provide political cover for others to speak out on it.

The table below shows how the distribution of seats would look if we used the D’Hondt formula and projected a seat tally for this new House of Lords using the actual results for each region from the 2024 general election. The regional results were amalgamated following the boundaries of our proposed regions.

Two hundred hereditary peers (the dignified bit)

During the first day of Queens Speech debates in the Lords in May 2010, the 13th Earl Ferrers said, in one of the most vivid speeches I recall ever hearing “We have witnessed today what must be the greatest constitutional spectacle in the world. Its majestic procession says a hundred and one things to all of us. The uniforms in all their glory have ensured the anonymity of the wearers. Gone are the Berts and Freds of normality. In their place, as we tiptoe back in history, come the glorious titles of Bluemantle Pursuivant, Rouge Dragon Pursuivant, Maltravers Herald Extraordinary. Then there are the Queen’s Body Guard, the Gentlemen at Arms and all the others. Each represents a facet of the constitution in which we all bask. We should never forget that. We live in a country full of history, traditions and peculiarities. Sometimes we get stroppy and want to change it all, but we should never forget that the intricate weave of the constitution and the majesty of the monarchy allow us flexibility to wriggle and to move within their confines. We must be careful not to snap the thread.”

New Labour tried hard to snap that thread in 1999. By introducing the House of Lords (Hereditary Peers) Bill it seems intent on completing the break. When considering what our second chamber should look like I do not believe it would be wise to leave out what we call the “dignified part”.

If New Labour succeed in removing the remaining the ninety-two hereditary peers, we should jolly well pledge to restore them as soon as possible, before the collective memory of how it is done fades and there are no longer any hereditary peers left who remember serving in the Lords.

After all, we can’t really call it the House of Lords if there aren’t any “real” peers there, can we? I propose we restore two hundred hereditary peers, selected, as now, from among the pool of hereditary peers, by hereditary peers, with the possible adaptation that we require a certain percentage be linked to a given nation or region of the United Kingdom.

We could, for example, have a system where if a Alba peer dies or retires, that seat must be taken up by another Alba peer. The number of peers assigned to each region could be set at 20 to reflect the elected element. A peer could qualify either due to having his title named for an area (i.e. Argyll), having his estate/seat in a given area (so the Duke of Devonshire could represent either Wessex or Mercia) or simply having a strong, demonstrable family link to an area.

Below is a table (prepared with the help of X.com’s “Grok”) showing examples of the hereditary peers that could be eligible for each region, including the location of their seat/estate. In theory there would be absolutely no problem finding enough peers for each region. Naturally, some of these peers would not be interested in serving in the Lords, but it’s worth knowing that we could get a good geographical spread at all ranks of the peerage.

This might also be an opportunity to tidy up the peerage a little itself. We might consider inviting certain peers who cannot maintain the dignities of a peerage the opportunity to renounce it, and possibly create some new ones to replace them. I will leave others to debate (or possibly demolish) the merits of this particular idea.

The crucial requirement will be to have a strong contingent of hereditary peers in the Lords, to set the tone for the rest and to make the Lords a chamber worthy of the name.

Two hundred appointed peers (the expert bit)

In addition to the two hundred elected and hereditary peers, we should continue being able to appoint some Peers on the basis of their expertise in a particular area, or to reflect special service to a particular cause, or to the nation itself. The House of Lords has benefitted from such people over the years and should continue doing so.

I propose a further two hundred appointed peers. These could be appointed for life as now or perhaps limited to a term set at something like twenty years, deliberately longer than a normal parliamentary term to promote continuity and to mirror the terms of elected peers.

Appointments would have to be taken entirely out of the hands of the government and handed to a genuinely independent panel, though there should be nothing to stop a government from making nominations. The shape and composition of the appointments panel is something that would have to be determined. I have no particular preference on this matter, so long as it’s fair.

As with the hereditary peers, these peers should have a strong geographical focus and so I propose that they also be linked to particular regions of the United Kingdom, with vacancies filled by people with strong links to that region and determined by a regional subcommittee in that region.

The aim here would be to continue to include people with serious expertise and dedication, whether that be legal, artistic, military, academic, medical or political. Whatever happens, the aim should be to deny opportunities for party cronyism.

The remaining fifty peers - The “Plus” Bit

Finally, in addition to the six hundred hereditary, appointed and elected “peers”, I propose we retain the twenty-six Church of England bishops, the Lords Spiritual, and restore the twelve Law Lords to their judicial function in the House of Lords. This would bring the total to six hundred and thirty-eight, just shy of the six hundred and fifty MPs in the Commons.

What to do with the remaining twelve seats?

If we are serious about achieving a symmetry and balance between the two Houses, I believe they should be equal in number. We can go about this in one of two ways; one conservative and one “wild card”.

Option A. – The conservative option

We give the hereditary peers an additional twelve seats. This means the two ex officiopeers, the hereditary Earl Marshall and the Lord Great Chamberlain have their positions protected as now and also means we can assign an additional ten seats to the hereditary peers.

These can either be assigned to each of the ten regions (one each) or they could be free floating seats to be filled by whoever the hereditary peers deem worthy.

This additional boost for the hereditary peers in effect gives the hereditary peers seniority in “their” House, but, thanks to the tripartite model, does not give them a majority.

Option B – the wild card option

After hiving off two for the ex officio hereditary peers as mentioned above, what if we deliberately treated ten these final twelve seats as modern-day “rotten boroughs”?

The exact way we could go about doing this is wide open for debate. We could the ten oldest universities in the country a seat to dispose of as they wished. These would be, in order of foundation date, the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge, St Andrews, Glasgow, Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Durham, London, Belfast and Aberystwyth. Each of the four nations would get at least one

Alternatively, we could have the seat allocated at random in a sort of lottery. Either way, we would achieve an element of randomness, intrigue and occasional outrage in their allocation.

Naturally I prefer Option A, but I thought it worth including the wild card to stimulate some additional debate.

Conclusion

I will leave it at this for now, in the hope of inviting people to contribute further to the refinement of this idea. As you will have detected, my primary concerns are maintaining a sense of constitutional balance and respect for our traditions, including the preservation and restoration of the rights of the hereditary peers.

I do not claim to have all the answers and I hope and expect there will be those reading this who can add to and improve on my ideas.

I do think my model would be a good way – possibly the only way – to come full circle on the constitutional tinkering first begun by New Labour in 1999 and in a way that doesn’t threaten to undermine the primacy of the House of Commons.

I also think it’s quite possibly the only model put forward so far which would recognise that the legitimacy of any system comes not just from democracy, but also from its longevity, from the affections of the public it serves and from the balance it provides.

I do not expect the hardcore leftists in Labour and elsewhere will like my idea. But they’ve now had twenty-six years to propose a solution that could command mass support and haven’t done so. If they still cannot get on board with something like my plan, we will at least have exposed their dogmatism on this issue.

Just as William the Marshal, Earl of Pembroke kicked the worst clauses of Magna Carta into the long grass and by doing so gifted the nation the document that still survives in part today, I see no reason why conservatives and restorationists today could not complete the job of Lords Reform, even if a part of that reform includes restoration of one major component of it.

I commend this plan to all traditionalists and restorationists.